Designing exploratory studies: measurement (part 2)

Remember Gelman’s preliminary principles for designing exploratory studies:

- Validity and reliability of measurements.

- Measuring lots of different things.

- Connections between quantitative and qualitative data.

- Collect or construct continuous measurements where possible.

I already wrote about validity and reliability. I admitted to not knowing enough yet to provide advice on assessing the reliability of measurements ecologists and evolutionists make (except in the very limited sense of whether or not repeated measurements of the same characteristic give similar results). For the time being that means I’ll focus on

- Remembering that I’m measuring an indicator of something else that is the thing that really matters, not the thing that really matters itself.

- Being as sure as I can that what I’m measuring is a valid and reliable indicator of that thing, even though the best I can do with that right now is a sort of heuristic connection between a vague notion of what I really think matters, underlying theory, and expectations derived from earlier work.

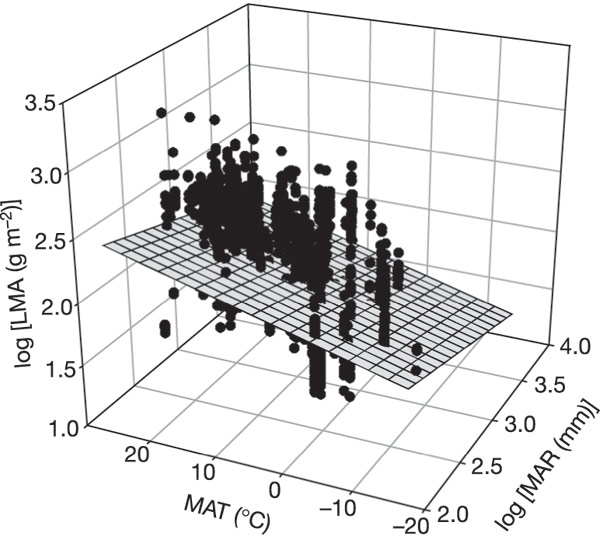

It’s that second part where “measuring lots of different things” comes in. Let’s go back to LMA and MAP. I’m interested in LMA because it’s an important component of the leaf economics spectrum. There are reasons to expect that tough leaves (those in which LMA is high) will not only be more resistant to herbivory from generalist herbivores, but that they will have lower rates of photosynthesis. Plants are investing more in those leaves. So high LMA is, in some vague sense, an indicator of the extent to which resource conservation is more important to plants than rapid acquisition of resources. So in designing an exploratory study, I should think about other traits plants have that could be indicators of resource conservation vs. rapid resource acquisition and measure as many of them as I can. A few that occur to me are leaf area, photosynthetic rate, leaf nitrogen content, leaf C/N ratio, tissue density, leaf longevity, and leaf thickness.

If I measure all of these (or at least several of them) and think of them as indicators of variation on the underlying “thing I really care about”, I can then imagine treating that underlying “thing I really care about” as a latent variable. One way, but almost certainly not the only way, I could assess the relationship between that latent variable and MAP would be to perform a factor analysis on the trait dataset, identify a single latent factor, and use that factor as the dependent variable whose variation I study in relation to MAP. Of course, MAP is only one way in which we might assess water availability in the environment. Others that might be especially relevant for perennials with long-lived leaves (like Protea) in the Cape Floristic Region rainfall seasonality, maximum number of days between days with “significant” rainfall in the summer, total summer rainfall, estimated potential evapotranspiration for the year, and estimated PET for the summer. A standard way to relate the “resource conservation” factor to the “water availability” factor would be a canonical correspondence analysis.

I am not advocating that we all start doing canonical correspondence analyses as our method of choice in designing exploratory studies, this way of thinking about exploratory studies does help me clarify (a bit) what it is that I’m really looking for. I still have work to do on getting it right, but it feels as if I’m heading towards something analogous to exploratory factor analysis (to identify factors that are valid, in the sense that they are interpretable and related in a meaningful way to existing theoretical constructs and understanding) and confirmatory factor analysis (to confirm that the exploration has revealed factors that can be reliably measured).

Stay tuned. It is likely to be a while before I have more thoughts to share, but as they develop, they’ll appear here, and if you follow along, you’ll be the first to hear about them.

Today is election day in the United States. The polls opened in Connecticut 2 hours ago, and there was a long line at my polling place by the time I arrived at 6:15.

Today is election day in the United States. The polls opened in Connecticut 2 hours ago, and there was a long line at my polling place by the time I arrived at 6:15.