There are three basic facts about genetic drift that I really want you to remember, even if you forget everything else I’ve told you about it:

Allele frequencies tend to change from one generation to the next purely as a result of random sampling error. We can specify a probability distribution for the allele frequency in the next generation, but we cannot specify the numerical value exactly.

There is no systematic bias to the change in allele frequency, i.e., allele frequencies are as likely to increase from one generation to the next as to decrease.

Populations will eventually fix for one of the alleles that is initially present unless mutation or migration introduces new alleles.

Natural selection introduces a systematic bias in allele frequency changes. Alleles favored by natural selection tend to increase in frequency. Notice that word “tend.” It’s critical. Because there is a random component to allele frequency change when genetic drift is involved, we can’t say for sure that a selectively favored allele will increase in frequency. In fact, we can say that there’s a chance that a selectively favored allele won’t increase in frequency. There’s also a chance that a selectively disfavored allele will increase in frequency in spite of natural selection.

We’re going to confine our studies to our usual simple case: one locus, two alleles. We’re also going to consider a very simple form of directional viability selection in which the heterozygous genotype is exactly intermediate in fitness.1

| \(A_1A_1\) | \(A_1A_2\) | \(A_2A_2\) |

| 1 + s | \(1 + \frac{1}{2}s\) | 1 |

After solving a reasonably complex partial differential equation, it can be shown that2 the probability that allele \(A_1\)3 is fixed, given that its current frequency is \(p\) is \[P_1(p) = \frac{1 - e^{-2N_esp}}{1 - e^{-2N_es}} \quad . \label{eq:beneficial}\] Now it won’t be immediately evident to you, but this equation actually confirms our intuition that even selectively favored alleles may sometimes be lost as a result of genetic drift. How does it do that? Well, it’s not too hard to verify that \(P_1(p) < 1\).4 The probability that the beneficial allele is fixed is less than one meaning that the probability it is lost is greater than zero, i.e., there’s some chance it will be lost.

How big is the chance that a favorable allele will be lost? Well, consider the case of a newly arisen allele with a beneficial effect. If it’s newly arisen, there is only one copy by definition. In a diploid population of \(N\) individuals that means that the frequency of this allele is \(1/2N\). Plugging this into equation ([eq:beneficial]) above we find \[\begin{aligned} P_1(p) &=& \frac{1 - e^{-2N_es(1/2N)}}{1 - e^{-2N_es}} \\ &\approx& 1 - e^{-N_es(1/N)} \hbox{ if $2N_es$ is ``large''} \\ &=& 1 - e^{s\left(\frac{N_e}{N}\right)} \\ &\approx& s\left(\frac{N_e}{N}\right) \hbox{ if $s$ is ``small.''} \end{aligned}\] In other words, most beneficial mutations are lost from populations unless they are very beneficial.5 If \(s=0.2\) in an ideal population, for example, a beneficial mutation will be lost about 80% of the time.6 Remember that in a strict harem breeding system with a single male \(N_e \approx 4\) if the number of females with which the male breeds is large enough. Suppose that there are 99 females in the population and one male. Then \(N_e/N = 0.04\) and the probability that this beneficial mutation will be fixed is only 0.8%.

Notice that unlike what we saw with natural selection when we were ignoring genetic drift, the strength of selection7 affects the outcome of the interaction. The stronger selection is the more likely it is that the favored allele will be fixed. In the case of a newly arisen allele, it’s also only the strength of selection that matters. Since a newly arisen allele is, by definition exists as only a single copy, it is very likely to be lost by chance. Once an a favorable allele has reached an appreciable frequency, the larger the population is, the more likely the favored allele will be fixed.8 Size does matter. But most favorable alleles are lost before they increase in frequency enough for the population size to matter.

If drift can lead to the loss of beneficial alleles, it should come as no surprise that it can also lead to fixation of deleterious ones. In fact, we can use the same formula we’ve been using (equation ([eq:beneficial])) if we simply remember that for an allele to be deleterious \(s\) will be negative. So we end up with \[P_1(p) = \frac{1 - e^{2N_esp}}{1 - e^{2N_es}} \quad . \label{eq:deleterious}\] One implication of equation ([eq:deleterious]) that should not be surprising by now is that even a deleterious allele can become fixed.9 Consider our two example populations again, an ideal population of size 100 (\(N_e = 100\)) and a population with 1 male and 99 females (\(N_e = 4\)). Remember, the probability of fixation for a newly arisen allele allele with no effect on fitness is \(1/2N = 5 \times 10^{-3}\) (Table 1).10

| \(N_e\) | ||

| \(s\) | 4 | 100 |

| 0.001 | \(4.9 \times 10^{-3}\) | \(4.5 \times 10^{-3}\) |

| 0.01 | \(4.8 \times 10^{-3}\) | \(1.5 \times 10^{-3}\) |

| 0.1 | \(3.2 \times 10^{-3}\) | \(2.2 \times 10^{-10}\) |

Genetic drift leads to the loss of genetic diversity over time.

Heterozygote advantage leads to the preservation of genetic diversity.

You might think that those facts would lead to the conclusion that drift would cause there to be less diversity than expected as a result of selection, but that selection would maintain diversity. It would be nice if the world were that simple. Unfortunately, it’s not.

The key to understanding why is to remember this basic fact: In a finite population there is a chance that in any generation one of the alleles that is segregating will be lost. In the absence of mutation or migration that introduces new genetic diversity into a finite population, that allele is lost forever. The end result is that any finite population will eventually lose its genetic diversity in the absence of mutation or migration, even one in which selection is “trying” to maintain diversity. Once you realize that, then you realize that the question isn’t “Will heterozygote advantage maintain genetic diversity in spite of genetic drift?” but “Will heterozygote advantage retard the inevitable loss of genetic diversity due to genetic drift?” The answer to that second questions is “It depends.”

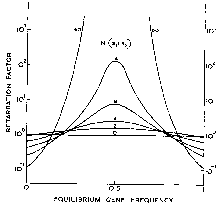

Specifically, Robertson showed that if selection would lead to an equilibrium allele frequency of between about 0.2 and 0.8, then it will tend to retard the loss of genetic diversity. If, however, selection would lead to a more extreme allele frequency, it will tend to increase the rate at which diversity is loss (Figure 1). While that result seems paradoxical at first, after a bit of reflection, it’s somewhat less surprising.

If an allele is relatively rare, drift will tend to dominate the dynamics of allele frequency change, even if it’s under selection.

If selection is “pushing” an allele to a relatively extreme frequency, it will get to the region where drift dominates the dynamics more rapidly than it would under drift alone.

So heterozygote advantage in which the two homozygotes have very asymmetrical fitnesses is likely to increase the rate at which diversity is lost. As a corollary, the allele in the disfavored homozygote is the most likely to be lost.

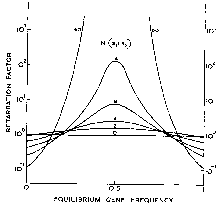

No. That’s not a typo. I meant to type “genetic draft.” Genetic draft is a term that John Gillespie coined to describe a phenomenon similar to genetic drift: If there is “a steady stream of adaptive substitutions at one locus\(\dots\), [then] the induced stochastic effects of the substitutions on [a linked] neutral locus can be faithfully captured in a one-locus model called the pseudohitchhiking model” He shows that the neutral locus shows dynamics that are quite different from what would be expected if it were not linked to the selective locus. The effects are illustrated in Figure 2

http://webdav.tuebingen.mpg.de/interference/draft.html;

accessed 27 February 2017).There are four properties of the interaction of drift and selection that I think you should take away from this brief discussion:

Most mutations, whether beneficial, deleterious, or neutral, are lost from the population in which they occurred.

If selection against a deleterious mutation is weak or \(N_e\) is small,11 a deleterious mutation is almost as likely to be fixed as neutral mutants. They are “effectively neutral.”12

If \(N_e\) is large, deleterious mutations are much less likely to be fixed than neutral mutations.

Even if \(N_e\) is large, most favorable mutations are lost.

If selection favors heterozygotes, it will retard the loss of genetic diversity only when the fitnesses of the two homozygotes are not greatly different from one another.

These notes are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License. To view a copy of this license, visit or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA.